NASA Mars Drone Testing and Robot Dogs: Building the Next Generation of Planetary Scouts

NASA Mars drone testing is opening a new chapter in how engineers prepare flying robots for the harsh realities of the Red Planet. By taking experimental drones into Earth’s most Mars-like deserts, NASA Mars drone testing teams can push navigation software, sensors, and flight hardware far beyond what is possible in a lab. From scorching heat to featureless sand dunes that confuse cameras, these environments help reveal exactly where current systems struggle and how next‑generation designs must evolve.

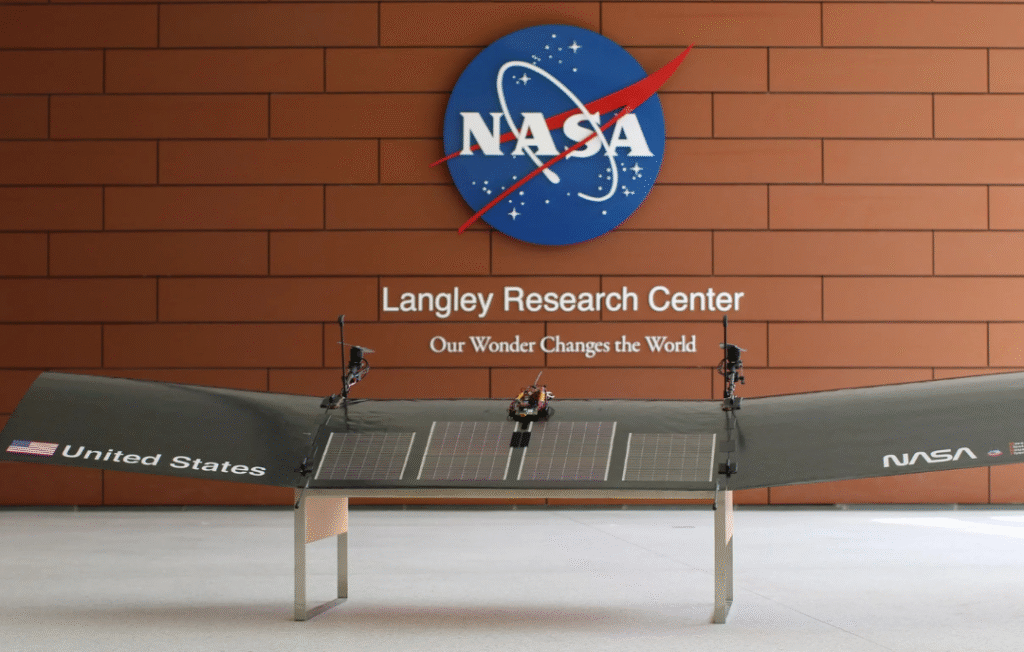

In recent field campaigns, NASA Mars drone testing has focused heavily on solving the challenges that grounded the first generation of aerial explorers. Engineers are trialing new autonomy algorithms that can handle low-texture terrain, experimenting with camera filters that improve ground tracking, and practicing precision landings in cluttered rocky areas. Each flight generates valuable data about stability, localization, and power management, feeding directly into the design of future helicopters, winged flyers, and hybrid concepts that will roam far beyond the reach of traditional rovers.

Crucially, NASA Mars drone testing is not just about individual aircraft, but about building a complete toolkit for planetary exploration. Lessons from desert flights inform how drones will coordinate with ground robots, scout ahead for human crews, and map scientifically rich but risky regions such as steep canyon walls or dune fields. As software matures and hardware proves itself in these analogue sites, NASA Mars drone testing brings the vision of agile, semi‑autonomous aerial scouts on Mars much closer to reality—promising richer science returns and safer operations for every future mission.

Why NASA Needs Drones for Mars Exploration

NASA needs drones for Mars exploration because they add an entirely new layer of mobility and perspective that orbiters and rovers alone cannot provide. While orbiters see the planet from far above and rovers crawl slowly over limited terrain, aerial vehicles can quickly scout cliffs, canyons, dune fields, and other hazards that are too risky or unreachable for wheeled robots. This extra “aerial dimension” helps mission teams plan safer routes, identify promising science targets, and understand the wider landscape around a landing site with far greater efficiency.

Drones also make exploration more efficient by covering much larger areas in less time. Ingenuity showed that a small helicopter can fly many kilometers, capture detailed images, and then guide a rover toward the most interesting rock layers or sediment deposits instead of forcing it to drive blind. Future NASA Mars drone testing aims to refine this scout role and expand it, allowing aircraft to carry miniaturized science instruments, survey potential landing zones, and even ferry small samples or tools between locations to support complex missions.

Finally, drones help de-risk future human exploration of Mars. Before astronauts ever walk on the surface, fleets of aerial scouts could map hazards, search for resources like accessible water ice, and monitor dust, weather, and terrain stability around planned bases and travel routes. By proving that powered, autonomous flight works reliably in the thin Martian atmosphere, NASA’s current work with helicopters and new flying concepts lays the groundwork for a future where aerial vehicles are standard partners to rovers and crews on the Red Planet.

Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy: Smarter Flight Software

Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy is the brains behind the next wave of NASA Mars drone testing, turning experimental aircraft from remote-controlled prototypes into truly self-reliant scouts. Instead of relying on constant instructions from Earth, this smarter flight software lets drones interpret their surroundings, decide how to respond to hazards, and keep flying safely even when terrain, lighting, or sensors become challenging. By pushing Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy in desert testbeds, NASA Mars drone testing teams are building the confidence needed to trust future flyers over Mars’ sand dunes, cliffs, and crater walls.

Vision beyond “perfect” terrain

Earlier helicopters struggled when flying over bland, low-texture landscapes like sand dunes. Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy teaches drones to handle these conditions by combining visual odometry with new camera settings, terrain models, and fallback logic when features disappear. This directly strengthens NASA Mars drone testing by making flights realistic to the wide, featureless regions common on the Red Planet.Smarter navigation and path planning

The software continuously evaluates where the drone is, how fast it is moving, and what obstacles lie ahead, then automatically adjusts its route. Instead of following a rigid script, the aircraft can tweak waypoints, altitudes, and speeds in real time. This adaptability is a core goal of NASA Mars drone testing, ensuring future vehicles can cope with unknown rocks, slopes, or dust without waiting for detailed commands from Earth.Robust landing-site selection

Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy includes logic to find and validate safe landing zones on the fly. By analysing slope, roughness, and available clearance, the drone can choose better touch-down spots than those pre-planned from orbital images alone. In NASA Mars drone testing campaigns, this reduces the risk of hard landings and mimics the decisions a Mars flyer will have to make far from its original takeoff point.Health monitoring and fail‑safe behaviours

The software keeps an eye on battery levels, sensor confidence, and control margins, then triggers behaviours like returning to base, slowing down, or entering hover when something looks wrong. This kind of self-protection is essential for NASA Mars drone testing, where every prototype flight must gather maximum data while protecting irreplaceable hardware.Higher-level autonomy for future missions

Ultimately, Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy is designed so operators can send high-level goals—“survey this dune field” or “map that canyon rim”—while the drone manages the detailed flying. As NASA Mars drone testing matures, this approach will allow small teams to supervise fleets of aerial scouts, dramatically expanding how much terrain can be explored and how much science can be returned from each mission window.

Robot Dogs and Ground Scouts for Hazardous Slopes

Robot dogs and other legged ground scouts are emerging as crucial partners for exploring hazardous slopes and unstable terrain on other worlds. Instead of relying solely on wheeled rovers, engineers are developing quadruped platforms that can climb loose sand, crusted soil, rocks, and icy patches while “feeling” the ground with every step. Projects such as LASSIE-M (Legged Autonomous Surface Science in Analogue Environments for Mars) show how motors in each leg can measure how much the surface sinks, slips, or pushes back, turning simple steps into data about regolith strength and hidden hazards.

In field tests at analogue sites like White Sands in New Mexico and Mount Hood in Oregon, robot dogs traverse steep dunes and rough volcanic slopes that would be risky for traditional rovers. Their proprioceptive sensing lets them adjust gait on the fly—shortening steps on soft patches, widening stance on crusty surfaces, or backing off when the ground becomes too unstable. At the same time, they can carry cameras and science instruments, scouting ahead of both humans and vehicles to map safe routes, flag high‑risk zones, and identify scientifically interesting changes in surface texture or ice content.

Deployed alongside aerial scouts and wheeled rovers, these legged ground robots form a multi‑layer safety system for hazardous slopes. Robot dogs can probe terrain before a rover attempts a climb, build “traversal risk maps” that mark soft or slippery regions, and even act as on‑the‑ground spotters for future astronaut crews. This combination of mobility, sensing, and autonomous decision‑making has the potential to prevent vehicles from getting stuck, expand access to cliffs and crater rims, and unlock new classes of science targets that have been off‑limits due to terrain risk.

Handling Sand Dunes, Heat and Featureless Landscapes

Handling sand dunes, extreme heat, and visually featureless terrain is central to NASA Mars drone testing because these conditions closely mimic some of the toughest environments on the Red Planet. When a drone flies over a rippled dune field with almost no rocks or shadows, its cameras struggle to lock onto visual features, making it harder to estimate speed and position. NASA Mars drone testing in deserts like Death Valley and the Mojave lets engineers deliberately fly over these bland landscapes and tune algorithms so that future Mars aircraft can stay stable, track their motion, and land safely even when the ground looks like an endless sheet of sand.

High temperatures and harsh winds are another reason Earth deserts are vital for NASA Mars drone testing. Electronics, motors, and batteries must function reliably despite scorching heat during the day and cooler temperatures at night, conditions that echo the thermal stress and dust exposure aircraft will face on Mars. By flying multiple sorties in these environments, engineers can see how sensors drift, how camera filters perform in glaring sunlight, and how well cooling and power systems hold up. This feedback drives refinements to both hardware and flight software so that the same designs can tolerate the thin, cold, dusty Martian atmosphere.

Finally, featureless landscapes force NASA Mars drone testing teams to lean more on autonomy and sensor fusion instead of manual piloting or perfect maps. Drones must combine inertial data, altitude readings, horizon detection, and sometimes terrain models to keep their bearings when the camera “goes blind” over smooth dunes. Lessons from these trials feed directly into Extended Robust Aerial Autonomy and similar software stacks, ensuring that the next generation of Mars flyers can cross dune seas, approach interesting outcrops, and return to base even when the surface below offers almost no visual clues.

How Field Data Improves Future Mars Missions

Field data is the bridge between ideas tested in simulations and reliable hardware operating on another planet. In NASA Mars drone testing, every flight in places like Death Valley or the Mojave Desert generates real-world measurements of temperature, wind, dust, lighting, navigation errors, battery performance, and landing precision. Engineers feed this field data back into models to refine aerodynamic designs, tune control laws, and update risk margins, so future Mars aircraft behave as predicted instead of surprising mission teams once they are millions of kilometers away.

NASA Mars drone testing also uses field data to improve software autonomy and sensing strategies. Logs from desert flights show exactly where vision-based navigation breaks down over featureless sand, how well different camera filters track ground texture, and which algorithms best pick safe landing spots in cluttered terrain. By replaying these real flights off-line, developers can benchmark new autonomy code against the same conditions, proving that each software upgrade is more robust than the last before it ever flies on Mars.

Finally, field data from NASA Mars drone testing informs how entire missions are designed and operated. Performance statistics help planners estimate realistic flight ranges, mapping coverage, and power budgets, which in turn shape landing-site choices and science timelines. Lessons from ground-robot and drone campaigns also guide how future Mars rovers, flyers, and even astronaut crews will work together—deciding when to send aerial scouts first, where to avoid soft dunes, and how to prioritize high‑value targets. In this way, field data steadily converts Mars exploration from a series of high-risk experiments into a more predictable, repeatable system.

Conclusion

Drones, robot dogs, and other experimental robots being tested in deserts and analogue sites on Earth are already reshaping how mission planners think about future Mars exploration. These field trials show that agile flyers and legged ground scouts can reach scientifically rich but hazardous terrain far beyond the safe operating envelope of traditional rovers, then feed back high‑value data to refine landing‑site choices, traverse plans, and instrument designs. Every successful test flight or slope climb on Earth reduces the uncertainty, risk, and cost of attempting the same feats millions of kilometers away.

Equally important, analogue campaigns generate the operational playbooks that future Mars crews and ground teams will rely on. By rehearsing real timelines, communication delays, and emergency procedures in these harsh environments, engineers and scientists discover which combinations of humans, rovers, aerial scouts, and legged robots deliver the best science return under realistic constraints. Lessons about team workflows, autonomy levels, and decision‑making tools are fed back into mission architecture, ensuring that upcoming Mars missions launch with strategies that have already been stress‑tested in the field.

Taken together, this steady “build a little, test a little, learn a lot” approach means that each new Mars mission will stand on the shoulders of thousands of hours of analogue experience. The more rigorously NASA uses Earth as a proving ground—flying drones over dune seas, sending robot dogs up treacherous slopes, and running long‑duration habitat simulations—the more confident we can be that future explorers, robotic and human alike, will have the resilient technologies and mature operations they need to work safely and productively on the Red Planet.